Sail Like Columbus: Using Dead Reckoning and Other Traditional Navigational Skills

In an age of GPS chartplotters and touchscreen multifunction displays, traditional navigation skills remain essential seamanship. Electronics can fail. Batteries can die. Signals can be lost. Knowing how to determine your position using dead reckoning and other time-tested methods not only builds confidence—it can be a lifesaver.

Whether you’re coastal cruising, passagemaking offshore, motoring out from marinas and private boat slip for rent or exploring rivers like the Seine, Rhine or St. Lawrence, traditional navigational skills provide a reliable backup and deepen your understanding of how your boat moves through the water.

What Is Dead Reckoning?

Dead reckoning (DR) is the process of estimating your current position based on:

- A known starting point

- Course steered

- Speed

- Time traveled

Using a nautical chart, you plot your starting position, draw a line in the direction of your compass heading and mark distance traveled based on speed and elapsed time.

Distance = Speed × Time

For example, if you travel at 6 knots for 2 hours, you’ve covered 12 nautical miles. On your chart, you measure 12 miles along your course line and mark your estimated position.

Dead reckoning assumes no influence from wind, current or tide. So, while it provides a solid estimate, it's rarely perfectly accurate over long distances.

Accounting for Set and Drift

To refine dead reckoning, navigators account for:

- Set: The direction a current pushes the vessel

- Drift: The speed of that current

By factoring in tidal or river current predictions, you can adjust your course to compensate. This creates an Estimated Position (EP), which is generally more accurate than pure DR.

On coastal waters or tidal rivers, failing to account for current can place you miles off track after several hours.

Piloting: Navigation by Visual Reference

Piloting uses visible landmarks and aids to navigation to determine position. It’s most common in coastal waters, harbors and inland waterways.

Common piloting tools include:

- Lighthouses and beacons

- Daymarks and buoys

- Church spires, towers or distinctive hills

- Bearings taken with a hand-bearing compass

By taking compass bearings on two or more known objects and plotting those lines on a chart, you can determine your exact position at their intersection. This method is called a fix.

Running Fixes

When only one visible object is available, navigators can use a running fix. This involves:

- Taking a bearing on a known object

- Continuing on course for a set time

- Taking a second bearing

- Plotting both bearings adjusted for distance traveled

The intersection reveals your position. It requires careful timekeeping and plotting accuracy.

The Role of the Magnetic Compass

The magnetic compass is the foundation of traditional navigation. Unlike electronic heading sensors, it requires no power and is remarkably reliable.

However, navigators must account for:

- Variation: The difference between magnetic north and true north (noted on charts)

- Deviation: Error caused by onboard electronics or metal

A deviation card near the helm helps correct for vessel-specific compass errors.

Speed Measurement: The Humble Log

Traditional navigation relies on accurate speed. Historically, sailors used a literal “log line”—a rope with knots tied at intervals—to measure speed. Today, boats typically use:

- Through-hull speed logs

- GPS speed-over-ground (as backup reference)

- RPM-based speed estimates (less precise)

Even without instruments, experienced boaters motoring out from private boat slip rentals near me can estimate speed by wake characteristics and engine sound. But plotting accuracy improves dramatically with reliable data.

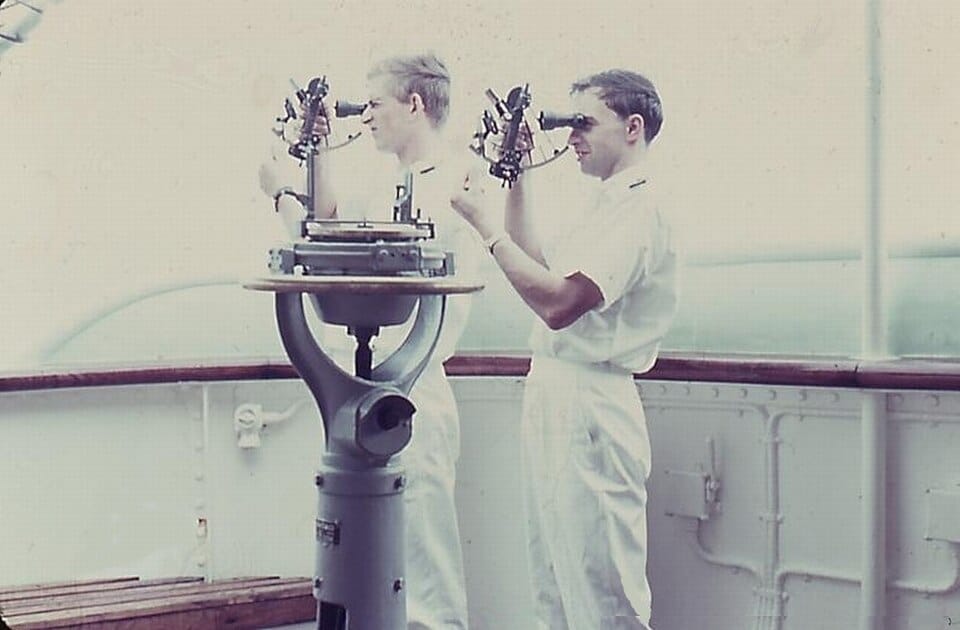

Celestial Navigation

Though less common among recreational boaters, celestial navigation remains a respected traditional method, particularly offshore. Using a sextant, accurate timepiece and nautical almanac, navigators measure the angle between celestial bodies (sun, moon, stars) and the horizon to determine latitude and longitude. While it requires training and practice, celestial navigation is completely independent of electronics. It’s a true self-sufficient skill.

Soundings and Depth Contours

Before sonar and depth sounders, mariners used lead lines to measure depth. Even today, depth contours on charts are critical navigational references.

By comparing:

- Charted depths

- Bottom composition notes

- Observed depth readings

You can cross-check your estimated position. This is particularly useful in fog or limited visibility.

Maintaining a Proper Logbook

Traditional navigation depends on disciplined recordkeeping. A proper log entry should include:

- Time (preferably in 24-hour format)

- Course steered

- Speed

- Distance run

- Weather conditions

- Engine RPM (if applicable)

- Position fixes when taken

Regular entries—every 30 to 60 minutes offshore and away from marinas or private boat docks for rent—allow you to reconstruct your position if needed.

Why Traditional Skills Still Matter

Modern GPS is extraordinarily accurate. But electronics can fail due to:

- Power loss

- Water intrusion

- Software malfunction

- Lightning strikes

Traditional navigation provides redundancy. More importantly, it cultivates situational awareness. When you understand course, current and distance intuitively, you become a more competent and confident skipper.

Many experienced passagemakers recommend practicing dead reckoning even when GPS is functioning—simply to keep skills sharp.

Blending Old and New

The smartest approach is not choosing between traditional and electronic navigation; it’s using both.

- Plot your GPS position on paper charts periodically.

- Maintain a DR track even when electronics are active.

- Verify electronic data with visual references.

This layered approach ensures safety and reinforces seamanship fundamentals.

The Enduring Value of Seamanship

Traditional navigation is more than a backup system, it’s part of boating heritage. From coastal cruisers to offshore sailors, understanding dead reckoning, piloting and celestial techniques connects modern mariners to centuries of seafaring knowledge.

Technology may guide the boat, but traditional skills guide the mariner, whether they’re cruising out from a marina or private boat lift rentals.